'' AAAWOOOEEEUUUOOO, PETE ... 'ear you bin to the States ... how wazzit?"

THE DISEMBODIED VOICE in the recreation room at Island's Basing Street studio gradually reveals itself as

emerging from a skinny and extremely stoned figure wearing a black leather jacket draped in a swirly-patterned,

table-cloth sized scarf who's stretched out of sight across four seats so he can get himself comfortable enough

to watch the TV. It's Mick Jones' way of relaxing and preparing himself for another twelve-hour day of laying

down the backing tracks for the second Clash album.

"Oh, the States was fun. I had a great time there."

"Shit. I'm really jealous."

"Go there for your holidays. You went to Jamaica last year; so you must be able to afford to go to the States

this year."

"Nah. When I go to the States for the first time, I want to do it properly - I only want to go as a member of a

group. That's the only way I wanna do it."

While he might have a very personal' conception of how to get himself in the correct frame of mind for

recording, Mick is as conscious as anybody of the current trend of opinion about the Clash. The nagging

implications that they were 'last year's thing, maaan' and maybe 'they weren't so hot even then' and 'anyway

punk's dead and these beat combos are much more fun so let's go and drink lemonade and tap our feet to that

groovy new love song'.

THE CLASH were always more than some people could take and now, in a changed climate, knives are being

sharpened that were kept well hidden while the Clash star was in the constant and meteoric ascendant, Some

say the Clash have become - or always were - punk's answer to the Bay City Rollers. Others have renounced

them in favour of Tom Robinson's more easily digestible agit-prop or the crass and banal 'sincereness' and

'street credibility' of Jimmy Pursey and his British Movement followers.

And the wait for the second Clash album. The wait, my God, the wait. If the Messiah was gonna take this long,

it'd halve the attendance at the synagogue overnight. Why so long? Reasons, reasons, all of them good ones.

But people don't care about reasons; they care about records.

Mick understands that. He knows and is unsurprisingly worried about it. In fact, he was apprehensive about my

doing this story as I'd already penned two long raves about the Clash - one when I reviewed the album last

year, the other in a very long article for Trouser Press - and he reckoned that I was about ready to do a

hatchet job on them. When I reminded him that I'd already given them a heavy slating for 'Clash City Rockers'

(wrongly, I now think), he seemed relieved.

What I didn't need to remind him about was that, despite all that sufferation, there's still hordes of eager fans

out there who must be just about at the stage of screaming to hear what the Clash are up to these days. After

all, it's certainly been a long time since there's been a more than halfway decent article on them in a music

paper. And, more than that, there hasn't been a serious in-depth interview with any of the band since the very

early days. The last one in Sounds was a non-communicative shambles done with Giovanni just before the start

of the Complete Control tour.

Arriving at Basing Street studios one hot afternoon, I was expecting to do both the interview and the pix within a

matter of a couple of hours. Postponing the interview because Joe was late and had to get straight into

recording, I ended up doing the first interview later that night - or rather the following morning - then going over

to Paris with them for a one-off gig and finishing up with another interview again done as the sun was rising.

So keeping it all in that order for the sake of simplicity, we begin with. . .

THE DISEMBODIED VOICE in the recreation room at Island's Basing Street studio gradually reveals itself as

emerging from a skinny and extremely stoned figure wearing a black leather jacket draped in a swirly-patterned,

table-cloth sized scarf who's stretched out of sight across four seats so he can get himself comfortable enough

to watch the TV. It's Mick Jones' way of relaxing and preparing himself for another twelve-hour day of laying

down the backing tracks for the second Clash album.

"Oh, the States was fun. I had a great time there."

"Shit. I'm really jealous."

"Go there for your holidays. You went to Jamaica last year; so you must be able to afford to go to the States

this year."

"Nah. When I go to the States for the first time, I want to do it properly - I only want to go as a member of a

group. That's the only way I wanna do it."

While he might have a very personal' conception of how to get himself in the correct frame of mind for

recording, Mick is as conscious as anybody of the current trend of opinion about the Clash. The nagging

implications that they were 'last year's thing, maaan' and maybe 'they weren't so hot even then' and 'anyway

punk's dead and these beat combos are much more fun so let's go and drink lemonade and tap our feet to that

groovy new love song'.

THE CLASH were always more than some people could take and now, in a changed climate, knives are being

sharpened that were kept well hidden while the Clash star was in the constant and meteoric ascendant, Some

say the Clash have become - or always were - punk's answer to the Bay City Rollers. Others have renounced

them in favour of Tom Robinson's more easily digestible agit-prop or the crass and banal 'sincereness' and

'street credibility' of Jimmy Pursey and his British Movement followers.

And the wait for the second Clash album. The wait, my God, the wait. If the Messiah was gonna take this long,

it'd halve the attendance at the synagogue overnight. Why so long? Reasons, reasons, all of them good ones.

But people don't care about reasons; they care about records.

Mick understands that. He knows and is unsurprisingly worried about it. In fact, he was apprehensive about my

doing this story as I'd already penned two long raves about the Clash - one when I reviewed the album last

year, the other in a very long article for Trouser Press - and he reckoned that I was about ready to do a

hatchet job on them. When I reminded him that I'd already given them a heavy slating for 'Clash City Rockers'

(wrongly, I now think), he seemed relieved.

What I didn't need to remind him about was that, despite all that sufferation, there's still hordes of eager fans

out there who must be just about at the stage of screaming to hear what the Clash are up to these days. After

all, it's certainly been a long time since there's been a more than halfway decent article on them in a music

paper. And, more than that, there hasn't been a serious in-depth interview with any of the band since the very

early days. The last one in Sounds was a non-communicative shambles done with Giovanni just before the start

of the Complete Control tour.

Arriving at Basing Street studios one hot afternoon, I was expecting to do both the interview and the pix within a

matter of a couple of hours. Postponing the interview because Joe was late and had to get straight into

recording, I ended up doing the first interview later that night - or rather the following morning - then going over

to Paris with them for a one-off gig and finishing up with another interview again done as the sun was rising.

So keeping it all in that order for the sake of simplicity, we begin with. . .

SOUNDS JUNE 17TH 1978

THE SERIOUS IN-DEPTH

INTERVIEW YOU'VE

BEEN WAITING FOR

PETE SILVERTON GETS THEM TO TALK.

CHALKIE DAVIS GETS THEM TO DRESS UP IN

SILLY CLOTHES AND POSE FOR PIX

THE SERIOUS IN-DEPTH

INTERVIEW YOU'VE

BEEN WAITING FOR

PETE SILVERTON GETS THEM TO TALK.

CHALKIE DAVIS GETS THEM TO DRESS UP IN

SILLY CLOTHES AND POSE FOR PIX

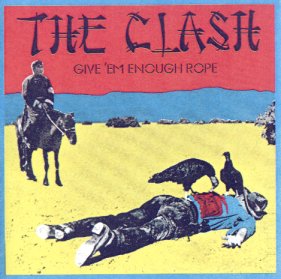

| SANDY PEARLMAN WITH MICK JONES & JOE STRUMMER DURING THE RECORDING OF 'GIVE EM ENOUGH ROPE'. |

THE STUDIO

WALKING DOWN the stairs for a short refreshment

break after nine hours in the studio, assistant producer

cum overseeing engineer, Corky Stasiak, turns to

Sandy Pearlman, Blue Oyster Cult mentor and now

Clash producer, and asks: "What did I do to deserve

this?"

Pearlman has no doubts: "You worked with Kiss. That's

what you did to deserve this."

After a while in the studio, I started to feel almost sorry

for these two American innocents abroad. Both used to

working with the most organised band in the world, they

are in a continual state of disbelief when confronted with

the most disorganised band in the world.

WALKING DOWN the stairs for a short refreshment

break after nine hours in the studio, assistant producer

cum overseeing engineer, Corky Stasiak, turns to

Sandy Pearlman, Blue Oyster Cult mentor and now

Clash producer, and asks: "What did I do to deserve

this?"

Pearlman has no doubts: "You worked with Kiss. That's

what you did to deserve this."

After a while in the studio, I started to feel almost sorry

for these two American innocents abroad. Both used to

working with the most organised band in the world, they

are in a continual state of disbelief when confronted with

the most disorganised band in the world.

While the Blue Oyster Cult drum roadie phones every day to confirm that everything's running smoothly and

report any minor hitches, it's a very good day when the Clash roadies manage to get the band to the studio on

time without forgetting to bring the guitars or something.

The Clash themselves seem to positively thrive on the spontaneity that this chaos enforces. They're past

masters of the British production technique - "Bash it down and we'll tart it up a bit later". Naturally, this

sometimes reduces the Americans to a state of utter dismay where all they can do is plead to the great god of

the recording studios somewhere up there in the sky above New York's Record Plant.

And yet the Clash's attitude to working in the studio - once they're actually in there and playing anyway - is very

disciplined, even militaristic. Strummer calls out "Hey, general" when he wants to speak to Pearlman and "Hey,

captain" when he's after Stasiak's attention. And, when I arrived at the studio, they'd just finished showing some

of the batch of war movies they'd got CBS to stump up for. . . after a little arm twisting - when CBS A&R chief,

Muff Winwood (or Duff Windbag as the Clash call him) had refused to pay for any more films, they phoned up

and informed him they knew where his car was parked; the films arrived the next day. Reinforcing this image of

them as an army unit, Strummer was continually goading everyone into action like some kind of musical section

leader.

(I asked him later about his almost quite dictatorial demeanour in the studio. "We arse around so much, you

know what I mean. We relax and laugh and joke and if you don't get down to it sometime, you'll never do it.")

But, while quasi-militaristic it might be, the Clash attitude is not quite the same concept of sta-prest organisation

that the Americans are used to.

report any minor hitches, it's a very good day when the Clash roadies manage to get the band to the studio on

time without forgetting to bring the guitars or something.

The Clash themselves seem to positively thrive on the spontaneity that this chaos enforces. They're past

masters of the British production technique - "Bash it down and we'll tart it up a bit later". Naturally, this

sometimes reduces the Americans to a state of utter dismay where all they can do is plead to the great god of

the recording studios somewhere up there in the sky above New York's Record Plant.

And yet the Clash's attitude to working in the studio - once they're actually in there and playing anyway - is very

disciplined, even militaristic. Strummer calls out "Hey, general" when he wants to speak to Pearlman and "Hey,

captain" when he's after Stasiak's attention. And, when I arrived at the studio, they'd just finished showing some

of the batch of war movies they'd got CBS to stump up for. . . after a little arm twisting - when CBS A&R chief,

Muff Winwood (or Duff Windbag as the Clash call him) had refused to pay for any more films, they phoned up

and informed him they knew where his car was parked; the films arrived the next day. Reinforcing this image of

them as an army unit, Strummer was continually goading everyone into action like some kind of musical section

leader.

(I asked him later about his almost quite dictatorial demeanour in the studio. "We arse around so much, you

know what I mean. We relax and laugh and joke and if you don't get down to it sometime, you'll never do it.")

But, while quasi-militaristic it might be, the Clash attitude is not quite the same concept of sta-prest organisation

that the Americans are used to.

In the studio proper, the band grouped around putting down the basic backing track live. Topper Headon

behind the screens with only his head showing as he bops up and down with the beat. Paul Simonon, legs

akimbo and bass slung low on his right hip while he punctuates his attack with a few casual spits at the floor.

Mick Jones lazes on a chair cuddled up round his Gibson Les Paul Special while Joe stands up, pumping his left

leg as always and shouting out the changes to the rest of them. Just like he looks onstage, in fact, apart from

one thing - his battered but trusty Telecaster is being mended and he's using a hired Gibson 345 instead, the

big cherry red semi-acoustic that's best known in the hands of Chuck Berry. Joe completes the illusion with the

occasional playful duck-walk.

behind the screens with only his head showing as he bops up and down with the beat. Paul Simonon, legs

akimbo and bass slung low on his right hip while he punctuates his attack with a few casual spits at the floor.

Mick Jones lazes on a chair cuddled up round his Gibson Les Paul Special while Joe stands up, pumping his left

leg as always and shouting out the changes to the rest of them. Just like he looks onstage, in fact, apart from

one thing - his battered but trusty Telecaster is being mended and he's using a hired Gibson 345 instead, the

big cherry red semi-acoustic that's best known in the hands of Chuck Berry. Joe completes the illusion with the

occasional playful duck-walk.

Meanwhile, up in the control room, unable to see what's happening in the studio (or be seen), Sandy and Corky

mix admirable professionalism with acapella choruses of the Olympics' 'Western Movies', discussions about how

great it'd be out on the beach in Long Island in this weather and, now and then, a deprecating comment about

what they've let themselves in for or, more often, what a lousy studio it is. Mostly though, the odd moment of

depression is tempered by admiration for the spirit of the band.

Pearlman refers to Topper in almost awed tones as "the rhythm machine. What have we done? A hundred

tracks? And he's only screwed up once." And, when they're not too busy eating one of the several ethnic meals

they send out for each night, they clearly respect Joe's drive and spirited animation, even if they can often

hardly make out one word of what he's singing. They canal so get very frustrated by the band's more casual

approach to the finer points of recording technology. In a break from blowing bubbles with his gum, Corky

noticed a small mistake on Paul's bass track. Paul couldn' t hear it all.

Joe could but still wondered: "'Why can't we leave it as it is?"

Pearlman: "Because people will notice."

Joe: "Only ten million Hitlers will notice."

Pearlman half-smiles, re-adjusts his baseball cap and shrugs

resignedly.

Joe: "Anyway, you won't even be able to hear it once I shout over it

a bit."

Mick: "And I'll be twanging over it.'

The bass part is redone.

SUCH ARE THE pains of aiming for perfecting and such are the

lengths to which the band will go to ensure that this second album encompasses both what they and the record

company (i.e. the American alburn-buying public) want and expect.

Considering that the first album has now sold somewhere in the region of a hundred thousand copies (and is

still selling very strongly for a year-old album), this might seem an open and shut case of two much green

leading to too much worry. But consider - ignoring the fact that all the band would love to be really famous rock

and roll stars - that none of their singles has done as well as might be expected and that they're all still on a

ridiculous twenty-five quid plus rent a week and matters move into a little more accurate perspective.

And Joe doesn't even have any rent to pay.

mix admirable professionalism with acapella choruses of the Olympics' 'Western Movies', discussions about how

great it'd be out on the beach in Long Island in this weather and, now and then, a deprecating comment about

what they've let themselves in for or, more often, what a lousy studio it is. Mostly though, the odd moment of

depression is tempered by admiration for the spirit of the band.

Pearlman refers to Topper in almost awed tones as "the rhythm machine. What have we done? A hundred

tracks? And he's only screwed up once." And, when they're not too busy eating one of the several ethnic meals

they send out for each night, they clearly respect Joe's drive and spirited animation, even if they can often

hardly make out one word of what he's singing. They canal so get very frustrated by the band's more casual

approach to the finer points of recording technology. In a break from blowing bubbles with his gum, Corky

noticed a small mistake on Paul's bass track. Paul couldn' t hear it all.

Joe could but still wondered: "'Why can't we leave it as it is?"

Pearlman: "Because people will notice."

Joe: "Only ten million Hitlers will notice."

Pearlman half-smiles, re-adjusts his baseball cap and shrugs

resignedly.

Joe: "Anyway, you won't even be able to hear it once I shout over it

a bit."

Mick: "And I'll be twanging over it.'

The bass part is redone.

SUCH ARE THE pains of aiming for perfecting and such are the

lengths to which the band will go to ensure that this second album encompasses both what they and the record

company (i.e. the American alburn-buying public) want and expect.

Considering that the first album has now sold somewhere in the region of a hundred thousand copies (and is

still selling very strongly for a year-old album), this might seem an open and shut case of two much green

leading to too much worry. But consider - ignoring the fact that all the band would love to be really famous rock

and roll stars - that none of their singles has done as well as might be expected and that they're all still on a

ridiculous twenty-five quid plus rent a week and matters move into a little more accurate perspective.

And Joe doesn't even have any rent to pay.